I want to show you a story from the Arizona Republic newspaper that specifically addresses the topic above. But, before doing that, I want to provide some context.

I have been reading and listening to many intelligent arguments, pro and con, about sending kids back to school. In general, the two sides build their cases around competing risks, those for keeping kids at home, those for sending them back into the classroom.

As you read through these arguments, it seems clear that a school location provides secondary value that stretches well beyond the explicit objectives and processes of conventional teaching. Perhaps the first step out from this impasse is to acknowledge this as an unintended consequence of American schooling. While these secondary values cannot be confined to childcare and to meals, these two needs are almost always included in the arguments to get kids back to school.

As I thought through this, I concluded that there was merit to the arguments on both sides of this issue. But we are faced with the practical matter that action is also required, so what should we do?

One approach would be to address this in very specific steps. My analytical model would open with a two-part position to, first, start school 100% remote and, second, figure out what to do about the secondary values that are associated with going to school.

Interestingly, we know how to teach in school and we now know a lot more about how to teach remotely. But we probably have never really focused on the smartest way to provide the secondary values that accompany going to school, especially since some of these services were not imagined when the existing teaching/school paradigm was designed. For example, until COVID-19, you did not explicitly hear people say that our schools are providing, for example, childcare. Now we know, however, that the loss of these services is a very big deal to many, many parents.

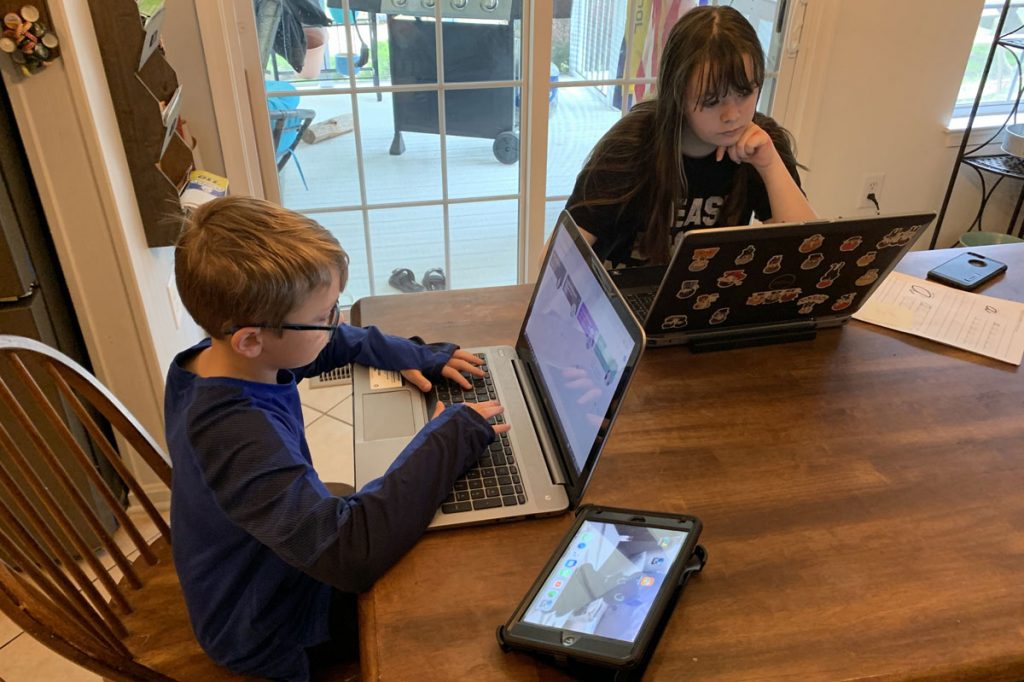

What are some of these secondary benefits? Childcare. Meals. Mental health support. The availability of tools, such as computers or pads. Personal safety. What else?

Which of these services are actually important enough to worry about? That is, we are discussing a fundamental re-think of a school’s mission forced on us by COVID-19. This is a very serious and needs very careful thinking. Might it be time to accept that a core reason for going to school is to receive these services?

And if we get by this step, we may need to identify and evaluate any creative alternative that can bring these services to children, both within the school system and without it.

If we were to address this analytically and write up some form of a project plan it might look like this:

First, start schooling remotely.

Second, identify the ten biggest issues associated with remote schooling, for example, the absence of childcare and of food.

Third, build acceptance that these are core issues and that schooling in a COVID-19 age needs to include services that address these issues as much as teaching history, or math, or science.

Fourth, conduct a thorough analysis of these issues and for each find an alternative that works. For example, given the infrastructure and given the teachers and administrators, how can the school specifically accommodate the child-care issue? Can we imagine a new paradigm where such students would, in effect, be studying from home, but their home would be inside the school building, configured to meet CDC guidelines of social distancing? Teacher involvement would be somewhat like parental involvement – navigation of systems. Help with exception situations.

Fifth, analytically work through the top ten list and find the best options for re-purposing the school to address the issue.

The simple fact may be that childcare, food, mental health counseling, technology tools, and other such services may be as essential to the child as what is taught in the classroom. Recognizing this, not as an accident but as a real purpose, would be the first step.

The Arizona school system is apparently already moving in this direction. What follows are major excerpts from today’s edition, August 19, 2020, of the Arizona Republic, page 8A, “Schools across the state open for children who need on-site support”, reported by Lorraine Longhi and Joshua Bowling:

Arizona schools all opened in some capacity Monday, but most offered the minimum level of in-person options the state allowed.

The criteria for students who qualified to take advantage of the in-person services were broad, and many districts and charter operators opened their campuses to any student who needed a safe place to go.

Priority was given to students with disabilities, English-language learners, students who qualify for free and reduced lunch, children in foster care, students without reliable access to technology and students whose parents are essential workers.

The on-site programs are not traditional classroom setups.

The support is intended to provide students with a space to study, a reliable internet connection to access their virtual classes, and adult supervision during normal school hours. The programs are expected to continue until schools reopen for in-person learning. (This was) Arizona’s first day of schools offering support spaces for students to participate in virtual classes.

At Scottsdale’s Coronado High School, the lecture hall was set up for students in sixth through 12th grades who needed a safe, supervised place to learn.

Margaret Serna, the executive director for Title I schools in the district, said the district opened Coronado and Saguaro high schools in south Scottsdale for on-site support because those were the areas that were expected to have the greatest demonstrated need.

Principal Amy Palatucci said that as of May, 76% of the school’s students qualified for free and reduced lunch.

Staff had prepared for up to 100 students to show up. But by 7:30 a.m., none of the 35 students who had registered for a spot at Coronado had arrived.

At 7:12 a.m. Elizabeth Ray watched the bus arrive to pick up her children for the first day of on-site support services at Verrado Middle School in the Litchfield Elementary school district.

Ray has a daughter in first grade and a son in fourth grade, both with Individualized Education Programs. Ray said Monday was the first day since the start of the semester that her son hasn’t thrown a tantrum related to his online schooling.

She described the smile on her son’s face, underneath his protective face shield, as he watched the bus arrive.

“He was genuinely smiling,” Ray said. “It was a smile that I hadn’t seen since before March.”

Ray said the opportunity for on-site support services has been a blessing, particularly as a parent of two special education students.

The district decided last week to postpone discussions on returning to in-person classes after data metrics from the Arizona Department of Health Services showed no county in the state had met the recommended benchmarks to reopen.

But for parents like Ray, the current model for distance learning is not working.

Ray said Monday was the first day that neither of her children cried during the school day. Her son woke up, knew that he needed to get ready for school and started his routine, she said.

“If this gives my kids some form of control over an otherwise crappy situation…I’m completely okay with it,” she said.

At Lincoln Elementary School in west Mesa, a handful of students and parents were lined up outside of the school at 8 a.m. to take advantage of the school’s services.

Karli Park was among them, dropping off her two children for the day. Park has a son with an IEP and a neurotypical daughter.

Park lives in Chandler, seven miles away from the school, and works full time as a social worker. She said online schooling has been difficult for her family. The online learning model reads out lessons in a “robot voice,” making it particularly difficult for her son to process, she said….

On Monday, she said staff at Lincoln seemed to be keeping the learning area clean and socially distanced, and she was comforted that her children would be sitting together, thanks to a policy by the school to group children from the same family together.

Park said she and her husband would support and empower their children to ultimately make the decision about which learning model they prefer.

But she still said it was a no-win situation, particularly for low-income families and English learners that have less support when making difficult decisions about whether to prioritize their children’s safety or their education.

“I think everyone just needs to understand, just empathy-wise, there are parents that are going to have to make the choice to put their kids in an unsafe situation,” Park said. “Really, we’re pushed into a corner.”

How the services work

Most districts and schools required that parents register their students beforehand, to plan for social distancing requirements.

School instruction is not provided at the on-site support locations. Instead, students receive supervision and assistance with their online classes from support staff. Schools asked that students bring their district-issued device and headphones to complete their online schoolwork.

Students are required to wear masks, though some districts will make exceptions for students in self-contained special education classes, students incapable of physically removing a mask or students with medical conditions preventing them from safely wearing a mask.

Districts are not providing transportation to the on-site support services, except for some districts like Peoria Unified and Litchfield Elementary that are providing transportation for special education students in self-contained, specialized programs.

Many of the districts are providing free and reduced-price lunch for students, or will have breakfast and lunch available to purchase, though some districts have asked parents to provide lunch for their students.

Some only keeping select schools open

Mesa Public Schools, the largest district in the state, opened on-site support centers at 26 of its schools. Registration is accepted until space at each site is filled.

The Chandler Unified School District is providing on-site support at all of its schools Monday through Friday during school hours. Chandler Online Academy students may attend support services at their home school.

Tucson Unified is providing services at all of its schools to “high needs” or “at risk” students, including self-contained Exceptions Education students, McKinney Vento homeless, refugee and foster care students.

All of BASIS charter schools and Legacy Traditional schools opened for on-site support services.

Peter Bezanson, CEO of BASIS, said that demand for on-site support services has been “highly variable,” but that they have seen the greatest demand at schools with a greater number of low-income students, like their south Phoenix location, where 75% of the students qualify for free and reduced lunch.

Have a tip out of schools? Reach the reporter Lorraine Longhi at llonghi@gannett.com or 480-243-4086. Follow her on Twitter @lolonghi.